Reading – The Elephant Man ➣Download Descarga

♪ with audio

Oxford Bookworms Library – Level 1

audios by chapters

02 The Card

03 A Letter To ‘The Times’

04 Merrick’s First Home

05 An Important Visitor

06 Outside The Hospital

07 The Last Letter

Reading – Discriminatory language ➣Download Descarga

Reading – Leisure with animals ➣Download Descarga

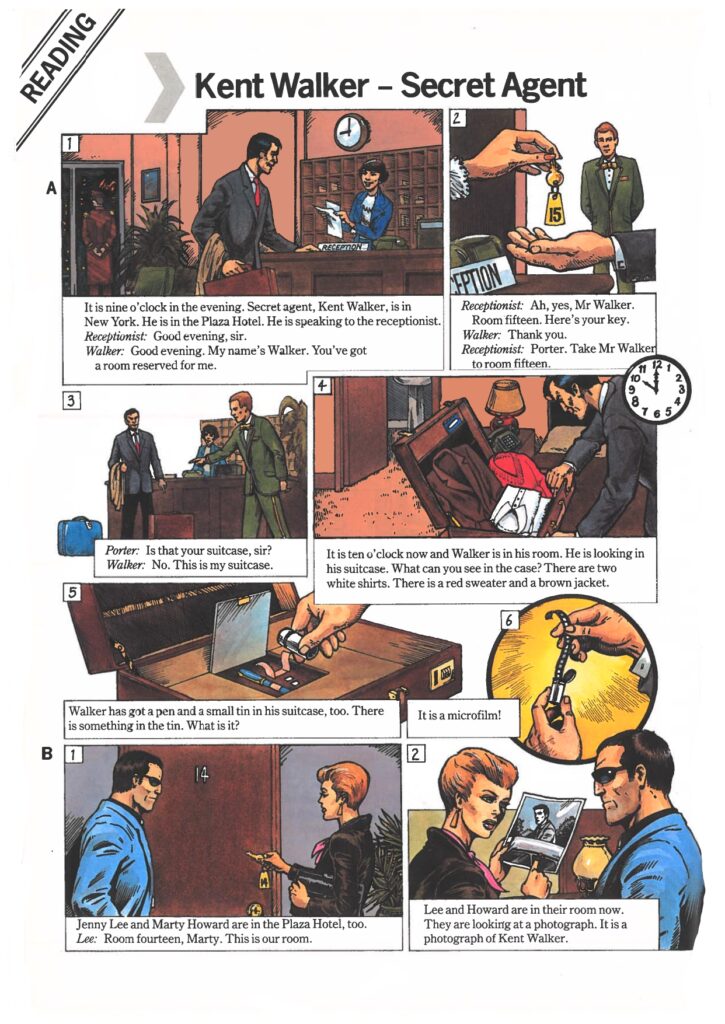

Reading – Elementary ➣ Present Tense

reference: New Generation Colin Granger Heinemann

Reading – Elementary ➣ Present Tense

Read about Tomas from Vienna – Answer True/False questions

Reading – Elementary ➣ Past Tense

Martin’s Vacation – Question/Answer Match

Reading – Full text ➣ Texto íntegro

four extracts from two autobiographies, a play and a dystopia

MY EARLY LIFE BY WINSTON S. CHURCHILL

I was to go to school. I was now seven years old,…I was also excited and agitated by this great change in my life. I thought in spite of the lessons, it would be fun living with so many other boys, and that we should make friends together and have great adventures. Also I was told that ‘school days were the happiest time in one’s life.’

The school my parents had selected for my education was one of the most fashionable and expensive in the country. It modelled itself upon Eton and aimed at being preparatory for that Public School above all others. It was supposed to be the very last thing in schools. Only ten boys in a class; electric light (then a wonder); a swimming pond; spacious football and cricket grounds; two or three school treats, or ‘expeditions’ as they were called, every term; the masters all M.A.’s in gowns and mortar-boards; a chapel of its own; no hampers allowed; everything provided by the authorities. It was a dark November afternoon when we arrived at this establishment. We had tea with the Headmaster, with whom my mother conversed in the most easy manner. I was preoccupied with the fear of spilling my cup and so making ‘a bad start.’ I was also miserable at the idea of being left alone among all these strangers in this great, fierce, formidable place. After all I was only seven, and I had been so happy in my nursery with all my toys. I had such wonderful toys: a real steam engine, a magic lantern, and a collection of soldiers already nearly a thousand strong. Now it was to be all lessons. Seven or eight hours of lessons every day except half-holidays, and football or cricket in addition.

When the last sound of my mother’s departing wheels had died away, the Headmaster invited me to hand over any money I had in my possession. I produced my three half-crowns, which were duly entered in a book, and I was told that from time to time there would be a ‘shop’ at the school with all sorts of things which one would like to have, and that I could choose what I liked up to the limit of the seven and sixpence. Then we quitted the Headmaster’s parlour and the comfortable private side of the house, and entered the more bleak apartments reserved for the instruction and accommodation of the pupils. I was taken into a Form Room and told to sit at a desk. All the other boys were out of doors, and I was alone with the Form Master. He produced a thin greeny-brown, covered book filled with words in different types of print.

‘You have never done any Latin before, have you?‘ he said.

‘No, sir.’

‘This is a Latin grammar.’ He opened it at a well-thumbed page. ‘You must learn this,’ he said, pointing to a number of words in a frame of lines. ‘I will come back in half an hour and see what you know.’

Behold me then on a gloomy evening, with an aching heart, seated in front of the First Declension.

- Mensa ➮ a table

- Mensa ➮ O table

- Mensam ➮ a table

- Mensae ➮ of a table

- Mensae ➮ to or for a table

- Mensa ➮ by, with or from a table

What on earth did it mean? Where was the sense in it? It seemed absolute rigmarole to me. However, there was one thing I could always do: I could learn by heart. And I thereupon proceeded, as far as my private sorrows would allow, to memorise the acrostic-looking task which had been set me.

In due course the Master returned.

‘Have you learnt it?’ he asked.

‘I think I can say it, sir,’ I replied; and I gabbled it off.

He seemed so satisfied with this that I was emboldened to ask a question.

‘What does it mean, sir?’

‘It means what it says. Mensa, a table. Mensa is a noun of the First Declension. There are five declensions. You have learnt the singular of the First Declension.’

‘But,’ I repeated, ‘what does it mean?’

‘Mensa means a table,‘ he answered.

‘Then why does mensa also mean O table,’ I enquired, ‘and what does O table mean?’

‘Mensa, O table, is the vocative case,’ he replied.

‘But why O table?’ I persisted in genuine curiosity.

‘O table,—you would use that in addressing a table, in invoking a table.‘ And then seeing he was not carrying me with him, ‘You would use it in speaking to a table.’

‘But I never do,’ I blurted out in honest amazement.

‘If you are impertinent, you will be punished, and punished, let me tell you, very severely,’ was his conclusive rejoinder.

Such was my first introduction to the classics from which, I have been told, many of our cleverest men have derived so much solace and profit.

Vocabulario

the masters all M.A.’s in gowns and mortar-boards ➣los profesores todos licenciados con sus togas y birretes.

no hampers allowed ➣no se permitían cestas de comida

It seemed absolute rigmarole to me ➣me pareció un perfecto galimatías

I could learn by heart ➣lo podía aprender de memoria

I was emboldened to ask a question ➣me envalentoné para formular una pregunta

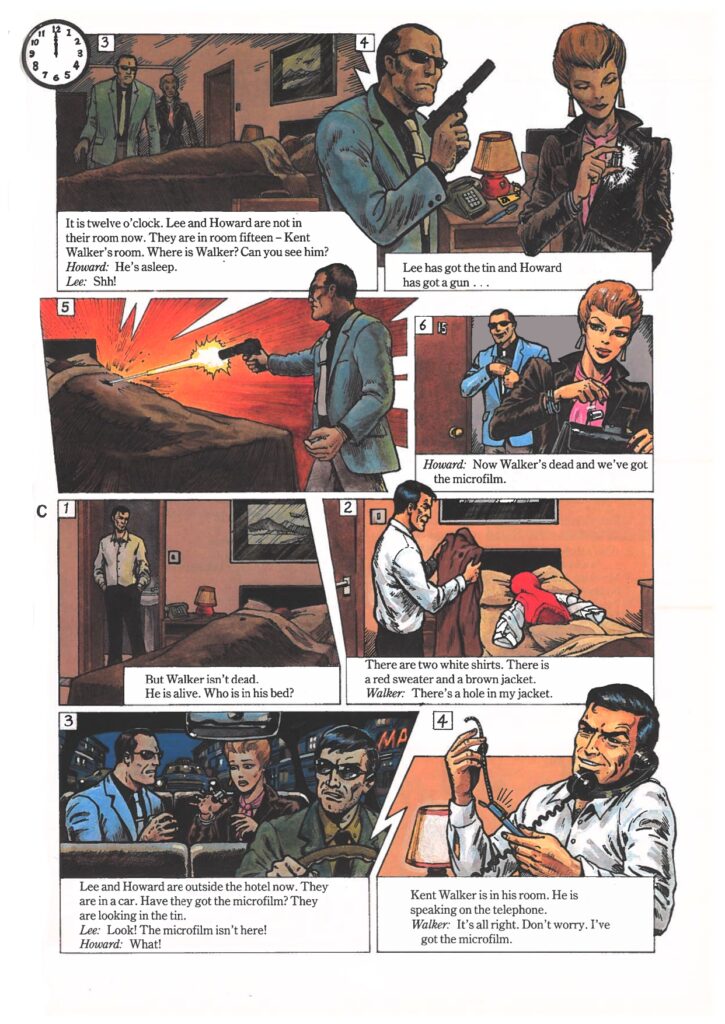

Memories of a Catholic Girlhood by Mary McCarthy

Published in 1957, this autobiography begins with McCarthy’s recollections of an indulgent, idyllic childhood tragically altered by the death of her parents in the influenza epidemic of 1918. She and her three younger brothers, and all four grandparents survived. In the 1918 pandemic, a disproportionate percentage of victims were young adults. The narration is imbued with a passionate sense of justice and the portrayal of her ghastly Cinderella childhood.

Whenever we children came to stay at my grandmother’s house, we were put to sleep in the sewing room, a bleak, shabby, utilitarian rectangle, more office than bedroom, more attic than office, that played to the hierarchy of chambers the role of a poor relation.

It was a room seldom entered by the other members of the family, seldom swept by the maid, a room without pride; the old sewing machine, some cast-off chairs, a shadeless lamp, rolls of wrapping paper, piles of cardboard boxes that might someday come in handy, papers of pins, and remnants of material united with the iron folding cots put out for our use and the bare floor boards to give an impression of ruthless temporality.

Thin white spreads, of the kind used in hospitals and charity institutions, and naked blinds at the windows reminded us of our orphaned condition and of the ephemeral character of our visit; there was nothing here to encourage us to consider this our home.

Poor Roy’s children, as commiseration damply styled us, could not afford illusions, in the family opinion. Our father had put us beyond the pale by dying suddenly of influenza and taking our young mother with him, a defection that was remarked on with horror and grief commingled, as though our mother had been a pretty secretary with whom he had wantonly absconded into the irresponsible paradise of the hereafter. Our reputation was clouded by this misfortune.

VOCABULARIO

we were put to sleep in the sewing room ➣ nos ponían a dormir en el cuarto de la costura

that played to the hierarchy of chambers the role of a poor relation ➣ (habitación) que, dentro de la jerarquía de las piezas de la casa, desempeñaba el papel de pariente pobre

could not afford illusions ➣ no nos podíamos permitir tener ilusiones

had put us beyond the pale ➣ nos había dejado en la estacada

defection ➣deserción

as though our mother had been a pretty secretary with whom he had wantonly absconded into the irresponsible paradise of the hereafter. ➣ como si nuestra madre hubiera sido una guapa secretaria con la que él se hubiese fugado impúdicamente al irresponsable paraíso del más allá.

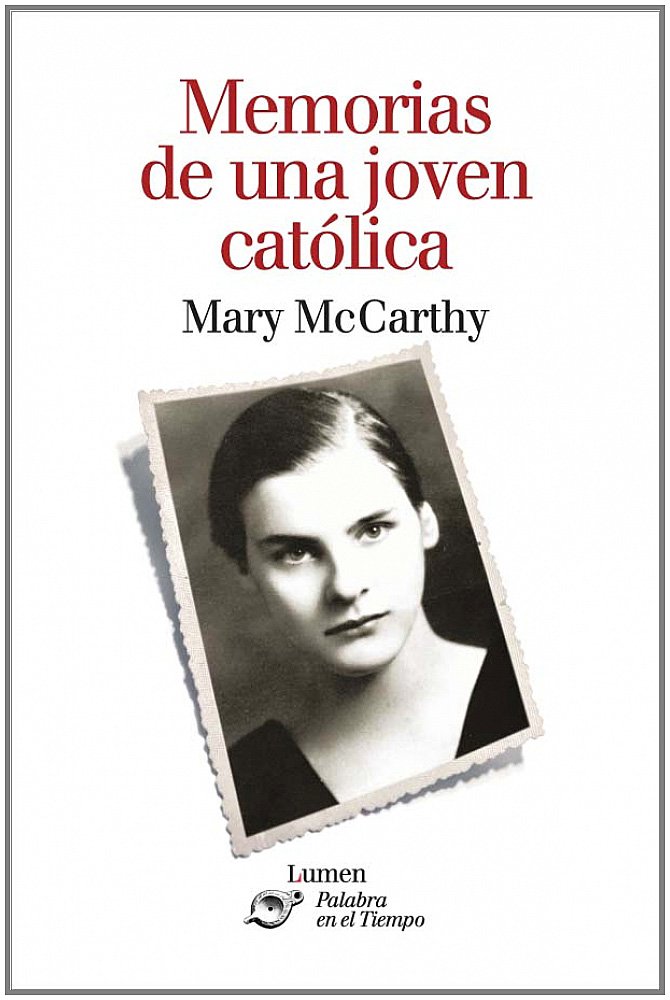

The Importance of Being Earnest A Trivial Comedy for Serious People BY Oscar Wilde

FIRST ACT

Lady Bracknell. [Pencil and note-book in hand.] I feel bound to tell you that you are not down on my list of eligible young men, although I have the same list as the dear Duchess of Bolton has. We work together, in fact. However, I am quite ready to enter your name, should your answers be what a really affectionate mother requires. Do you smoke?

Jack. Well, yes, I must admit I smoke.

Lady Bracknell. I am glad to hear it. A man should always have an occupation of some kind. There are far too many idle men in London as it is. How old are you?

Jack. Twenty-nine.

Lady Bracknell. A very good age to be married at. I have always been of opinion that a man who desires to get married should know either everything or nothing. Which do you know?

Jack. [After some hesitation.] I know nothing, Lady Bracknell.

Lady Bracknell. I am pleased to hear it. I do not approve of anything that tampers with natural ignorance. Ignorance is like a delicate exotic fruit; touch it and the bloom is gone. The whole theory of modern education is radically unsound. Fortunately in England, at any rate, education produces no effect whatsoever. If it did, it would prove a serious danger to the upper classes, and probably lead to acts of violence in Grosvenor Square. What is your income?

Jack. Between seven and eight thousand a year.

Lady Bracknell. [Makes a note in her book.] In land, or in investments?

Jack. In investments, chiefly.

Lady Bracknell. That is satisfactory. What between the duties expected of one during one’s lifetime, and the duties exacted from one after one’s death, land has ceased to be either a profit or a pleasure. It gives one position, and prevents one from keeping it up. That’s all that can be said about land.

(Entre los deberes que se esperan de uno en la vida y los deberes que se le exigen después de la muerte, la tierra ha dejado de ser en todo caso un beneficio o un placer. Proporciona a uno posición pero le impide mantenerla. Eso es todo lo que puede decirse de la tierra).

Jack. I have a country house with some land, of course, attached to it, about fifteen hundred acres, I believe; but I don’t depend on that for my real income. In fact, as far as I can make out, the poachers are the only people who make anything out of it.

Lady Bracknell. A country house! How many bedrooms? Well, that point can be cleared up afterwards. You have a town house, I hope? A girl with a simple, unspoiled nature, like Gwendolen, could hardly be expected to reside in the country.

Jack. Well, I own a house in Belgrave Square, but it is let by the year to Lady Bloxham. Of course, I can get it back whenever I like, at six months’ notice.

Lady Bracknell. Lady Bloxham? I don’t know her.

Jack. Oh, she goes about very little. She is a lady considerably advanced in years.

Lady Bracknell. Ah, nowadays that is no guarantee of respectability of character. What number in Belgrave Square?

Jack. 149.

Lady Bracknell. [Shaking her head.] The unfashionable side. I thought there was something. However, that could easily be altered.

Jack. Do you mean the fashion, or the side?

Lady Bracknell. [Sternly.] Both, if necessary, I presume. What are your politics?

Jack. Well, I am afraid I really have none. I am a Liberal Unionist.

Lady Bracknell. Oh, they count as Tories. They dine with us. Or come in the evening, at any rate. Now to minor matters. Are your parents living?

Jack. I have lost both my parents.

Lady Bracknell. To lose one parent, Mr. Worthing, may be regarded as a misfortune; to lose both looks like carelessness. Who was your father? He was evidently a man of some wealth. Was he born in what the Radical papers call the purple of commerce, or did he rise from the ranks of the aristocracy?

Jack. I am afraid I really don’t know. The fact is, Lady Bracknell, I said I had lost my parents. It would be nearer the truth to say that my parents seem to have lost me . . . I don’t actually know who I am by birth. I was . . . well, I was found.

Lady Bracknell. Found!

Jack. The late Mr. Thomas Cardew, an old gentleman of a very charitable and kindly disposition, found me, and gave me the name of Worthing, because he happened to have a first-class ticket for Worthing in his pocket at the time. Worthing is a place in Sussex. It is a seaside resort.

Lady Bracknell. Where did the charitable gentleman who had a first-class ticket for this seaside resort find you?

Jack. [Gravely.] In a hand-bag.

Lady Bracknell. A hand-bag?

Jack. [Very seriously.] Yes, Lady Bracknell. I was in a hand-bag–a somewhat large, black leather hand-bag, with handles to it–an ordinary hand-bag in fact.

Lady Bracknell. In what locality did this Mr. James, or Thomas, Cardew come across this ordinary hand-bag?

Jack. In the cloak-room at Victoria Station. It was given to him in mistake for his own.

Lady Bracknell. The cloak-room at Victoria Station?

Jack. Yes. The Brighton line.

Lady Bracknell. The line is immaterial. Mr. Worthing, I confess I feel somewhat bewildered by what you have just told me. To be born, or at any rate bred, in a hand-bag, whether it had handles or not, seems to me to display a contempt for the ordinary decencies of family life that reminds one of the worst excesses of the French Revolution. And I presume you know what that unfortunate movement led to? As for the particular locality in which the hand-bag was found, a cloak-room at a railway station might serve to conceal a social indiscretion–has probably, indeed, been used for that purpose before now–but it could hardly be regarded as an assured basis for a recognised position in good society.

Jack. May I ask you then what you would advise me to do? I need hardly say I would do anything in the world to ensure Gwendolen’s happiness.

Lady Bracknell. I would strongly advise you, Mr. Worthing, to try and acquire some relations as soon as possible, and to make a definite effort to produce at any rate one parent, of either sex, before the season is quite over.

Jack. Well, I don’t see how I could possibly manage to do that. I can produce the hand-bag at any moment. It is in my dressing-room at home. I really think that should satisfy you, Lady Bracknell.

Lady Bracknell. Me, sir! What has it to do with me? You can hardly imagine that I and Lord Bracknell would dream of allowing our only daughter–a girl brought up with the utmost care–to marry into a cloakroom, and form an alliance with a parcel? Good morning, Mr. Worthing!

[Lady Bracknell sweeps out in majestic indignation.]

The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood

Synopsis:

First published in 1985, The Handmaid’s Tale is a novel of such power that the reader is unable to forget its images and its forecast. With more than two million copies in print, it is Margaret Atwood‘s most popular and compelling novel. Set in the near future, it describes life in what once was the United States, now called the Republic of Gilead. Reacting to social unrest, and a sharply declining birthrate, the new regime has reverted to — even gone beyond — the repressive tolerance of the original Puritans. Offred is a Handmaid who may leave the home of the Commander and his wife once a day to walk to food markets whose signs are now pictures instead of words because women are no longer allowed to read. She must lie on her back once a month and pray that the Commander makes her pregnant because she is only valued as long as her ovaries are viable. Offred can remember the years before, when she lived and made love with her husband, Luke; when she played with and protected her daughter; when she had a job, money of her own, and access to knowledge. But all of that is gone now. Funny, unexpected, horrifying, and altogether convincing, The Handmaid’s Tale is at once scathing satire, dire warning, and tour de force.

Night

CHAPTER 1

We slept in what had once been the gymnasium. The floor was of varnished wood, with stripes and circles painted on it, for the games that were formerly played there; the hoops for the basketball nets were still in place, though the nets were gone. A balcony ran around the room, for the spectators, and I thought I could smell, faintly like an afterimage, the pungent scent of sweat, shot through with the sweet taint of chewing gum and perfume from the watching girls, felt-skirted as I knew from pictures, later in miniskirts, then pants, then in one earring, spiky green-streaked hair. Dances would have been held there; the music lingered, a palimpsest of unheard sound, style upon style, an undercurrent of drums, a forlorn wail, garlands made of tissue-paper flowers, cardboard devils, a revolving ball of mirrors, powdering the dancers with a snow of light.

margin note – «I could smell, […] the pungent scent of sweat, […] with the sweet taint of chewing gum and perfume from the watching girls» – El sentido del olfato, sense of smell, muy presente en esta situación angustiosa, in this distressing situation.

margin note –«felt-skirted […] mini-skirted […] spiky green hair» – These female fashions represent the fifties, sixties and seventies respectively. Offred is about thirty years old in the 1980s.

There was old sex in the room and loneliness, and expectation, of something without a shape or name. I remember that yearning, for something that was always about to happen and was never the same as the hands that were on us there and then, in the small of the back, or out back, in the parking lot, or in the television room with the sound turned down and only the pictures flickering over lifting flesh.

We yearned for the future. How did we learn it, that talent for insatiability? It was in the air; and it was still in the air, an after-thought, as we tried to sleep, in the army cots that had been set up in rows, with spaces between so we could not talk. We had flannelette sheets, like children’s, and army-issue blankets, old ones that still said U.S. We folded our clothes neatly and laid them on the stools at the ends of the beds. The lights were turned down but not out. Aunt Sara and Aunt Elizabeth patrolled; they had electric cattle prods slung on thongs from their leather belts.

No guns though, even they could not be trusted with guns. Guns were for the guards, specially picked from the Angels. The guards weren’t allowed inside the building except when called, and we weren’t allowed out, except for our walks, twice daily, two by two around the football field, which was enclosed now by a chain-link fence topped with barbed wire. The Angels stood outside it with their backs to us. They were objects of fear to us, but of something else as well. If only they would look. If only we could talk to them. Something could be exchanged, we thought, some deal made, some tradeoff, we still had our bodies. That was our fantasy.

We learned to whisper almost without sound. In the semi-darkness we could stretch out our arms, when the Aunts weren’t looking, and touch each other’s hands across space. We learned to lip-read, our heads flat on the beds, turned sideways, watching each other’s mouths. In this way we exchanged names, from bed to bed: Alma. Janine. Dolores. Moira. June.

Shopping

CHAPTER 2

A chair, a table, a lamp. Above, on the white ceiling, a relief ornament in the shape of a wreath, and in the center of it a blank space, plastered over, like the place in a face where the eye has been taken out. There must have been a chandelier, once. They’ve removed anything you could tie a rope to.

A window, two white curtains. Under the window, a window seat with a little cushion. When the window is partly open — it only opens partly — the air can come in and make the curtains move. I can sit in the chair, or on the window seat, hands folded, and watch this. Sunlight comes in through the window too, and falls on the floor, which is made of wood, in narrow strips, highly polished. I can smell the polish. There’s a rug on the floor, oval, of braided rags. This is the kind of touch they like: folk art, archaic, made by women, in their spare time, from things that have no further use. A return to traditional values. Waste not want not. I am not being wasted. Why do I want?

margin note – «A return to traditional values»: This was a catchphrase of 1980s conservatism. It was particularly associated in America with the Presidency of Ronald Reagan, and in the U.K. with Margaret Thatcher. In the U.S.A., an important aspect to the movement was an alliance between the political right wing and Evangelical Christianity.

On the wall above the chair, a picture, framed but with no glass: a print of flowers, blue irises, watercolor. Flowers are still allowed, Does each of us have the same print, the same chair, the same white curtains, I wonder? Government issue?

Think of it as being in the army, said Aunt Lydia.

A bed. Single, mattress medium-hard, covered with a flocked white spread. Nothing takes place in the bed but sleep; or no sleep. I try not to think too much. Like other things now, thought must be rationed. There’s a lot that doesn’t bear thinking about. Thinking can hurt your chances, and I intend to last. I know why there is no glass, in front of the watercolor picture of blue irises, and why the window opens only partly and why the glass in it is shatterproof. It isn’t running away they’re afraid of. We wouldn’t get far. It’s those other escapes, the ones you can open in yourself, given a cutting edge.

So. Apart from these details, this could be a college guest room, for the less distinguished visitors; or a room in a rooming house, of former times, for ladies in reduced circumstances. That is what we are now. The circumstances have been reduced; for those of us who still have circumstances.

margin note –«ladies in reduced circumstances»: Unmarried pregnant women

But a chair, sunlight, flowers: these are not to be dismissed. I am alive, I live, I breathe, I put my hand out, unfolded, into the sunlight. Where I am is not a prison but a privilege, as Aunt Lydia said, who was in love with either/or.

margin note – «who was in love with either/or.» : Aunt Lydia saw things in either black or white, there is no gray area, either you behave, or you will be punished.

The bell that measures time is ringing. Time here is measured by bells, as once in nunneries. As in a nunnery too, there are few mirrors.

I get up out of the chair, advance my feet into the sunlight, in their red shoes, flat-heeled to save the spine and not for dancing. The red gloves are lying on the bed. I pick them up, pull them onto my hands, finger by finger. Everything except the wings around my face is red: the color of blood, which defines us. The skirt is ankle-length, full, gathered to a flat yoke that extends over the breasts, the sleeves are full. The white wings too are prescribed issue; they are to keep us from seeing, but also from being seen. I never looked good in red, it’s not my color. I pick up the shopping basket, put it over my arm.

The door of the room — not my room, I refuse to say my — is not locked. In fact it doesn’t shut properly. I go out into the polished hallway, which has a runner down the center, dusty pink. Like a path through the forest, like a carpet for royalty, it shows me the way.

The carpet bends and goes down the front staircase and I go with it, one hand on the banister, once a tree, turned in another century, rubbed to a warm gloss. Late Victorian, the house is, a family house, built for a large rich family. There’s a grandfather clock in the hallway, which doles out time, and then the door to the motherly front sitting room, with its flesh tones and hints. A sitting room in which I never sit, but stand or kneel only. At the end of the hallway, above the front door, is a fanlight of colored glass: flowers, red and blue.

There remains a mirror, on the hall wall. If I turn my head so that the white wings framing my face direct my vision towards it, I can see it as I go down the stairs, round, convex, a pier glass, like the eye of a fish, and myself in it like a distorted shadow, a parody of something, some fairy-tale figure in a red cloak, descending towards a moment of carelessness that is the same as danger. A Sister, dipped in blood.

At the bottom of the stairs there’s a hat-and-umbrella stand, the bentwood kind, long rounded rungs of wood curving gently up into hooks shaped like the opening fronds of a fern. There are several umbrellas in it: black, for the Commander, blue, for the Commander’s Wife, and the one assigned to me, which is red. I leave the red umbrella where it is, because I know from the window that the day is sunny. I wonder whether or not the Commander’s wife is in the sitting room. She doesn’t always sit. Sometimes I can hear her pacing back and forth, a heavy step and then a light one, and the soft tap of her cane on the dusty-rose carpet.

I walk along the hallway, past the sitting room door and the door that leads into the dining room, and open the door at the end of the hall and go through into the kitchen. Here the smell is no longer of furniture polish. Rita is in here, standing at the kitchen table, which has a top of chipped white enamel. She’s in her usual Martha’s dress, which is dull green, like a surgeon’s gown of the time before. The dress is much like mine in shape, long and concealing, but with a bib apron over it and without the white wings and the veil. She puts on the veil to go outside, but nobody much cares who sees the face of a Martha. Her sleeves are rolled to the elbow, showing her brown arms. She’s making bread, throwing the loaves for the final brief kneading and then the shaping.

Rita sees me and nods, whether in greeting or in simple acknowledgment of my presence it’s hard to say, and wipes her floury hands on her apron and rummages in the kitchen drawer for the token book. Frowning, she tears out three tokens and hands them to me. Her face might be kindly if she would smile. But the frown isn’t personal: it’s the red dress she disapproves of, and what it stands for. She thinks I may be catching, like a disease or any form of bad luck.

Sometimes I listen outside closed doors, a thing I never would have done in the time before. I don’t listen long, because I don’t want to be caught doing it. Once, though, I heard Rita say to Cora that she wouldn’t debase herself like that.